23 September 2021

6 February 2022

History, life and love in Paris in 130 photographs

When

23 September 2021

6 February 2022

Press Office

An exhibition dedicated to a fisherman: this is how the master of photography Robert Doisneau loved to call himself.

Together with Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Doisneau (1912-1994) is considered one of the founding fathers of French humanist photography and street photojournalism. With his lens he captures the daily life of the men and women who populate Paris and its banlieue, with all the emotions of the gestures and situations in which they are engaged. In 11 sections, the exhibition combines Doisneau’s chronology with a thematic approach, telling the story of more than 130 black and white gelatin silver prints from the collection of the Atelier Robert Doisneau in Montrouge. It is in this place that the photographer printed and archived his images for over fifty years, leaving a legacy of nearly 450,000 negatives.

The poetry of the everyday moment

Les frères, rue du Docteur Lecène, Paris 1934

The fisherman of moments

An exhibition dedicated to a fisherman. This is how he liked to call himself Robert Doisneau, a master of photography who was able to portray the Parisian society of the 20th century with empathy, capturing moments of grace and expressions of happiness. Artist or photojournalist, Doisneau has left us images capable of making us smile and, at the same time, shaking our hearts, for his approach to humanity was far more complex than the simple lightness that we tend to associate with his pictures. “Actually,” he said, “my true passion is fishing; photography is just a hobby”. The hobby of one of the past century’s greatest photographers.

All images are protected by copyright © Robert Doisneau

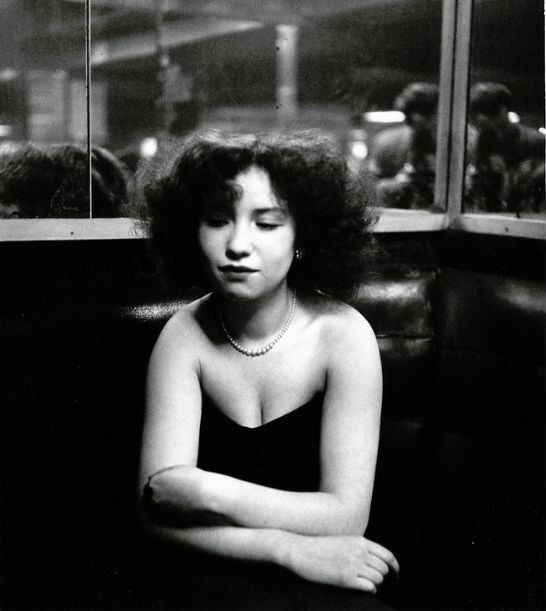

Cafè noir et blanc, 1948

Here it is, the Doisneau that the whole world loved. Theironic, touching, sedentary Doisneau at ease only in the periphery of Paris (and not even in all of them: only in those to the south). Whose favorite places were streets, factories, gatehouses and, as in this case, bistros.

Peripheries in which a peripheral humanity moves in which Doisneau, with empathy, showed the misery, the restlessness, the melancholy, however managing to capture the moments of grace, of happiness, the smiles of a moment.

Comtesse Gaëlle et Monsieur Pedro, 1950

Many exhibitions have been dedicated to Doisneau but this one is different, because the curator, Gabriel Bauret, has scanned the 450.000 negatives of the archive to distill a selection capable of outlining a full-lenght portrait of the artist: so yes, there are the essential shots but there are also little-known photos, which allow us to discover the lesser-known Doisneau. Like that of commissioned works.

Commissions made him uncomfortable, they forced him out of his shell: he was a sedentary who hated to leave his “periphery of him”. «I wasted a lot of energy» he will confess himself talking about those jobs. One can therefore imagine with what spirit, at the request of Vogue, in 1951 he left Paris to go to the Hôtel de Paris of Biarritz, to a gala dinner attended by also the two protagonists who give the title to this photo.

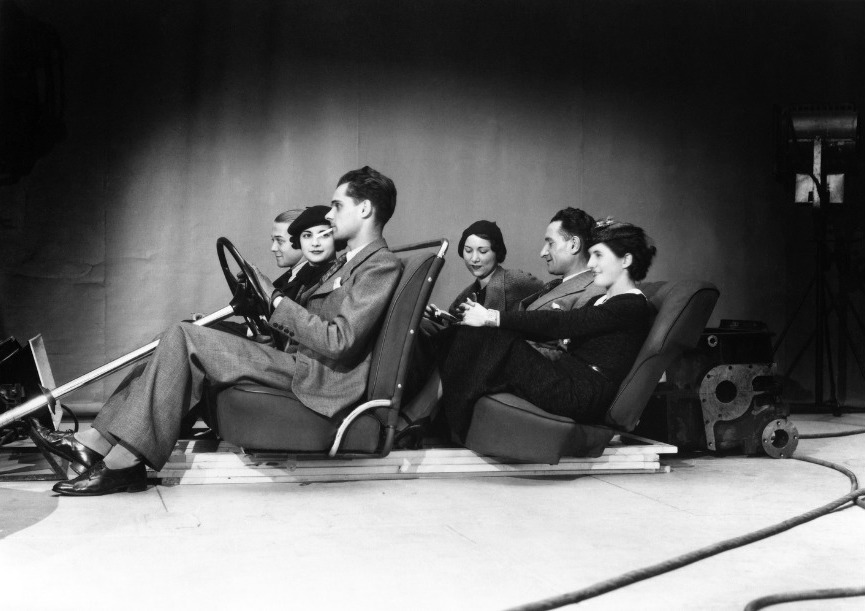

Prise de vues publicitaire Renault, 1935

Looking at this photo you can discover a couple of things that perhaps not everyone knows. The first, as can also be deduced from the title (Publicity shot for Renault, 1935) is that Doisneau also worked on commission. He did it early in his career and never stopped. One of the first clients was the iautomotive industry.

Between 1934 and 1939 he worked at Renault: five very formative years, during which he made various advertising shots that taught him to master the technique and take care of every detail, because nothing in those photos was left to chance.

However, there was another reason why Doisneau considered that experience important: in addition to the advertisements, in fact, Renault also asked him to document the activity of the Boulogne-Billancourt workshops. It was then that he discovered the reality of the working class conditions, to which he would have always felt close.

Mademoiselle Anita, 1951

What intrigues, in this photo, is not what you see but what you can glimpse. Over time, Robert Doisneau managed to overcome the innate shyness, which had led him to photograph people from a distance, and to find the famous “right distance” which, for him, it meant getting closer but never getting to a close-up. As in this portrait taken in Paris in 1951.

The choice of distance is crucial in the composition of a photo. Leaving a void at the edges of the frame was, in fact, a habit for photographers of his generation, and Doisneau himself made croppins to eliminate peripheral details that seemed superfluous to him. In this photo, for example, the detail considered superfluous was itself: thanks to a game of mirrors, in fact, the photographer can be seen not once but twice.

Les FFI de Ménilmontant, 1944

Can you see the irony in this photo? Yet there is. It is not seen because it is not the one intended by the author but it is the irony, so called, “of fate”. The day it was taken, Doisneau was walking through the beloved Parisian suburbs, near Ménilmontant. It wasn’t ordinary days, it was the summer of 1944 and Paris had just been liberated from the Nazis.

he stroller, in fact, but above all his camera, were noticed by a group of freshly won partisans: «Can you take us a picture?». Doisneau had only two rolls of film with him: a group portrait was the last thing he wanted to do. But how could he refuse?

And the irony? The irony of fate, as Francine revealed, is that, many years later, her father confessed that this very photo, which he had no intention of taking, was actually the best he had ever taken.

Promenade dominicale, 1934

Observing it with the eye of a detective like Auguste Dupin, this photo hides the revealing clue of an unsuspected character trait in a “street photographer” like Doisneau: shyness. The clue is distance, all those meters that separate the observing eye from the observed object: three women and two men, in the park, in their festive clothes.

Doisneau was empathic, a gift for a photographer, but also shy, an obstacle. He resolved the conflict by seeking, and finally finding the right distance, consistent with his temperament, between himself and the subjects he photographed, without ever getting too close to the faces.

In this the Rolleiflex helped him, allowing him to photograph without holding the camera at eye level, so the subject did not realize he was being photographed. «And yet I had the sensation of seeing people very well. So I launched myself, at the time the public did not refuse».

Le Fox Terrier du Pont des Arts, 1953

What you see is a story of looks: it begins with a dog looking at a photographer while her master looks at a painter, who in turn looks at a woman, dressed, but portrays her naked. It ends with an unresolved doubt about what the dog’s owner is really looking at.The shot was taken in Paris in 1953 and it’s a sleight of hand by the magician Robert Doisneau. Like all magic, it tells us two stories: one can be seen, the other not.

In the story that is not seen there is a great photographer, very good not only at seizing the moment, but also at inventing it. Unlike the magicians, however, Doisneau liked to reveal his tricks of him: “This is a completely constructed photo,” he said.

«We were a nice group in a café on rue de Seine, all a little tipsy; with us was a girl that the fellow painter wanted to portray on the Pont des Arts. I suggested he paint her naked, to see how people would react».

L’Enfer, 1952

A fisherman. This is how Robert Doisneau liked to call himself: «Actually», he commented, « my real passion is fishing: photography is just a hobby ». But then he concluded: «To be honest, fishing isn’t all that different from photography».

And so a joke about fishing turns out to be a truth about photography, which he called the “discipline of waiting“. Waiting, even for a long time, in order to be in the right place at the right time to seize the fish-moment with the hook of the lens.

Exactly what happened with the photo you see here: Doisneau took it in Paris, on the Boulevard de Clichy, in 1952, using the grotesque entrance of L’Enfer as a decoy. (from which it took its title), «a cabaret», he said, «where the bourgeois came to seek the thrill of the forbidden». He, on the other hand, went there to cast the hook.

Italiano

Italiano