Art, from Symbolism to the Avant-Garde

1 April 2021

4 July 2021

1 April 2021

4 July 2021

Is it really possible to hear music with your eyes? Is it possible to give shape to sound and color to the invisible? Questions like these have spawned a long history of relations between the visual and sound arts. We have explored them. And we are ready to tell you about them with a “polyphonic approach“. You will discover masterpieces by great masters such as Kandinsky, Renoir, Chagall, Klee, Kokoschka, Boccioni, Balla, Segantini, Casorati, as well as precious drawings by Picasso, Klimt and Le Corbusier. Music to your eyes!

Paul Emile Berthon, Mystical Concert, 1901

The theme of the relationships between music and the visual arts in the contemporary age has experienced renewed critical and historiographic success in recent decades. Starting with “Wagnerism“, a highly successful artistic vein that explicitly refers to the work and aesthetic doctrines of the great German composer, music was often an inspiring element for artists between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Examples can be identified among the Italian and foreign symbolists, the Viennese Secession, as well as the cubists – in particular Picasso and Braque – whose paintings with musical instruments offer an interesting reason for reflection and in the currents of Neoplasticism, Dadaism and Surrealism. If the sound component was central to Italian Futurism, it is however with Vasilij Kandinskij that music becomes an “absolute” element, becoming a model and paradigm of a painting that wants to free itself definitively from figurativism. “Vedere la Musica. Art, from Symbolism to the Avant-Garde” is the long history of relationships, intertwinings and correspondences. Highlighting the infinite, original facets of the interactions between the musical element and the visual arts. Proposing emblematic examples of both arts, thus creating an exhibition-show of absolute fascination.

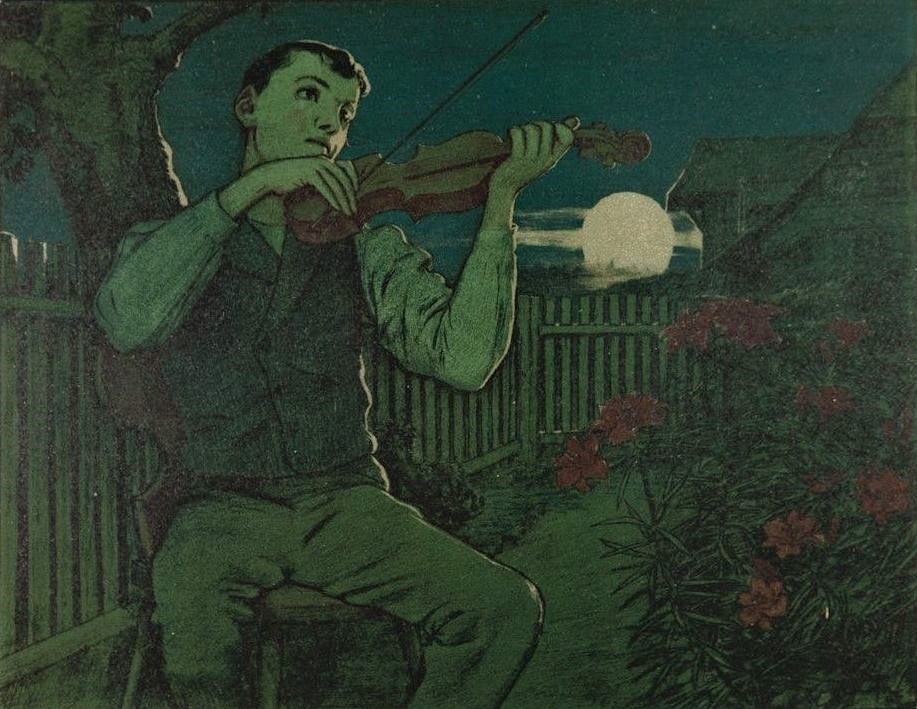

Hans Thoma, Violinist in the moonlight, 1897

Landscapes inspired by Chopin’s Nocturnes or Beethoven’s Claire de Lune, where physical reality is translated into images which envelop places and figures in a unity of harmonies and “chromatic symphonies”.

But also the legend of the composer as a mad, tormented hero. Titanic, like Richard Wagner, or cursed, like Beethoven.

Leo Putz, Parzifal, 1900

The evocative power of his dramas, his ideal of the “total work of art”, his persona itself, have inspired an endless production of paintings, prints, engravings, sculptures and illustrations.

Alois Kolb, Portrait of Beethoven, around 1909

the symbol of the mad, cursed musician, the misunderstood genius.

But Beethoven was more than just the man: the composer became the immobile, invisible engine of works in which the protagonist was his music, or even its absence.

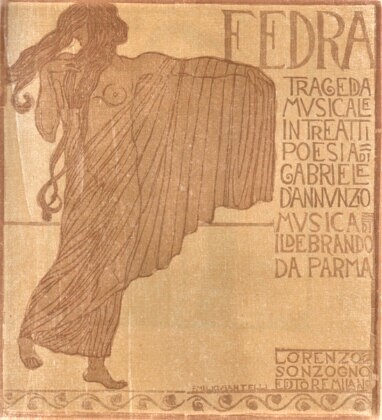

Emilio Mantelli, Fedra, 1913

The change in artistic sensibilities at the turn of the century also profoundly changed the way that passions were perceived, conveyed and represented, condemning opera to ever-lesser relevance.

In contrast to its decline, however, was the ascent of poster design: it was the golden age of opera posters, thanks both to advances in printing technology and the talent of artists such as Aleardo Villa, Adolfo De Carolis, Giuseppe Palanti and Leopoldo Metlicovitz.

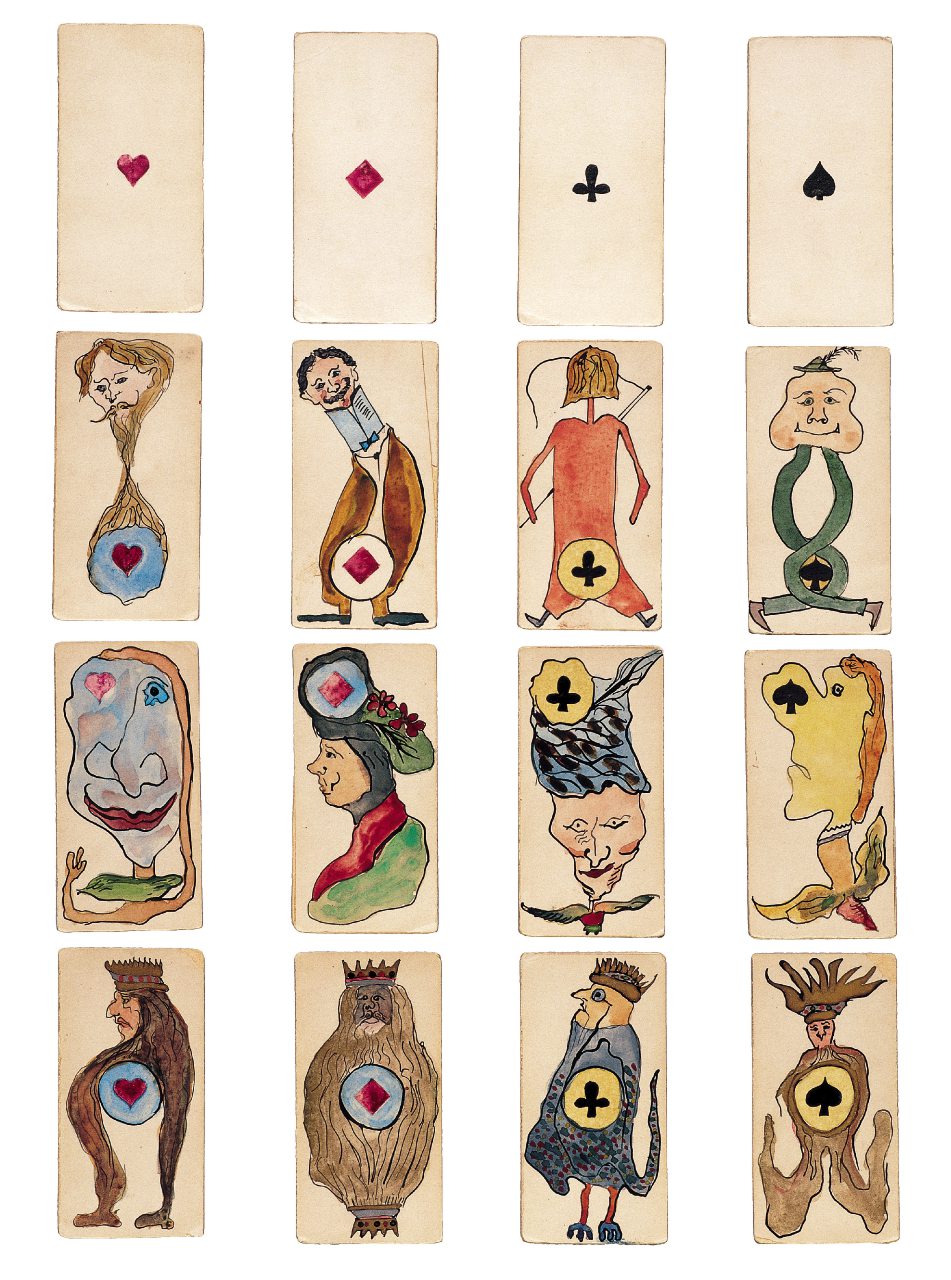

Arnold Schönberg, hand-made playing cards, 1909

an artistic, political, social and cultural revolution in Austria and Germany. For its exponents, music played a key role.

And so, with fascination for composer Franz Schubert added to that for Wagner and Beethoven, allegorical depictions flourished.

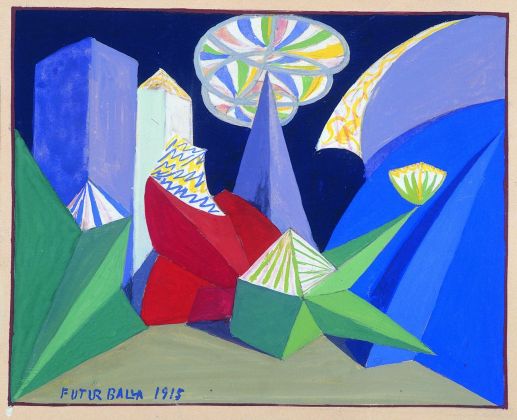

Giacomo Balla, sketch for “Feu d’Artifice”, 1917

Russolo, for example, as well as being a painter and engraver, was also a composer and creator of music requiring the use of “intonarumori”, specially constructed noise-generating machines.

Giacomo Balla, on the other hand, would design and create a console from which to manage the 76 combinations of coloured light which took the place of the dancers in his piece “balletto di sole luci” to the notes of Stravinsky.

Otto Gustaf Carlsund, Composition aux instruments dans un ovale, 1926

They also introduced the dimension of “time”, typically associated with music, to painting. Purism would come from the experience of Cubism, where “everything in a work of art should be and seem a pure resolution”.

The result? Works which present themselves as genuine architecture of objects, often musical instruments, constructed and laid out in accordance with harmonic schemes or geometrical and mathematical models.

Paul Klee, At night, 1921

The fascination exerted by the pure compositional cleanliness of his counterpoints, the idea of art without a subject, and the increasing renunciation of visual expression found acknowledgement in the aspiration of painting to reach the immaterialism and abstraction of his fugues.

Neoplasticism, with its search for rationality and purity of form, also features a significant musical presence, in particular in its references to visual rhythms.

Vasilij Kandinskij, The Great Gate of Kiev, 1928

While the titles of his paintings often incorporate the musical lexicon, in his writings the Russian artist developed the concept of “monumental art”, composed of the colour, sound and music of dance.

While the structure in a Kandinsky painting consists of colours brought together beyond any main note of harmony, in Schönberg’s compositions the lack of distinction between lines and colours corresponds to that between melody and harmony.

All this while Kupka continued his search to achieve a style of painting in which music becomes the model for a definitive liberation from the imitation of reality.